Text & Publications - Mehdi-Georges Lahlou

NL Mehdi-Georges Lahlou stelt vaak thema’s als culturele en religieuze identiteit, esthetiek en gender ter discussie. Hij buigt ze om, vindt ze opnieuw uit en ontkracht stereotypen om ze in een andere, nieuwe en intrigerende gedaante te laten terugkeren. Zijn sculpturen, installaties, performances, collages enz. slaan bruggen tussen het oosten en het westen, als een verwijzing naar zijn eigen meervoudige identiteit. Door het oog van de toeschouwer en zijn eigen cultuur komen zijn werken veelduidig over.

FR Mehdi-Georges Lahlou interroge régulièrement l’identité culturelle, religieuse, l’esthétique et le genre. Il les détourne, les repense, déjoue les stéréotypes pour les réincarner en une proposition neuve et interpellante. Au travers de sculptures, d’installations, de perfomances, de collages, etc. Il crée des passerelles entre Orient et Occident qui rappellent sa propre identité multiple. Ses oeuvres apparaissent polysémiques, interprétées par l’œil du spectateur et sa propre culture.

ENG Mehdi-Georges Lahlou regularly questions cultural and religious identity, aesthetics and gender. He diverts them, rethinks them, and thwarts stereotypes to reincarnate them in a new and challenging proposition. Through sculptures, installations, performances, collages, etc., he builds bridges between East and West that recall his own multiple identity. His work is polysemic, interpreted by the eye of the viewer and his own culture.

H ART over tentoonstelling Behind the Garden, Botaniek Brussel, 2017

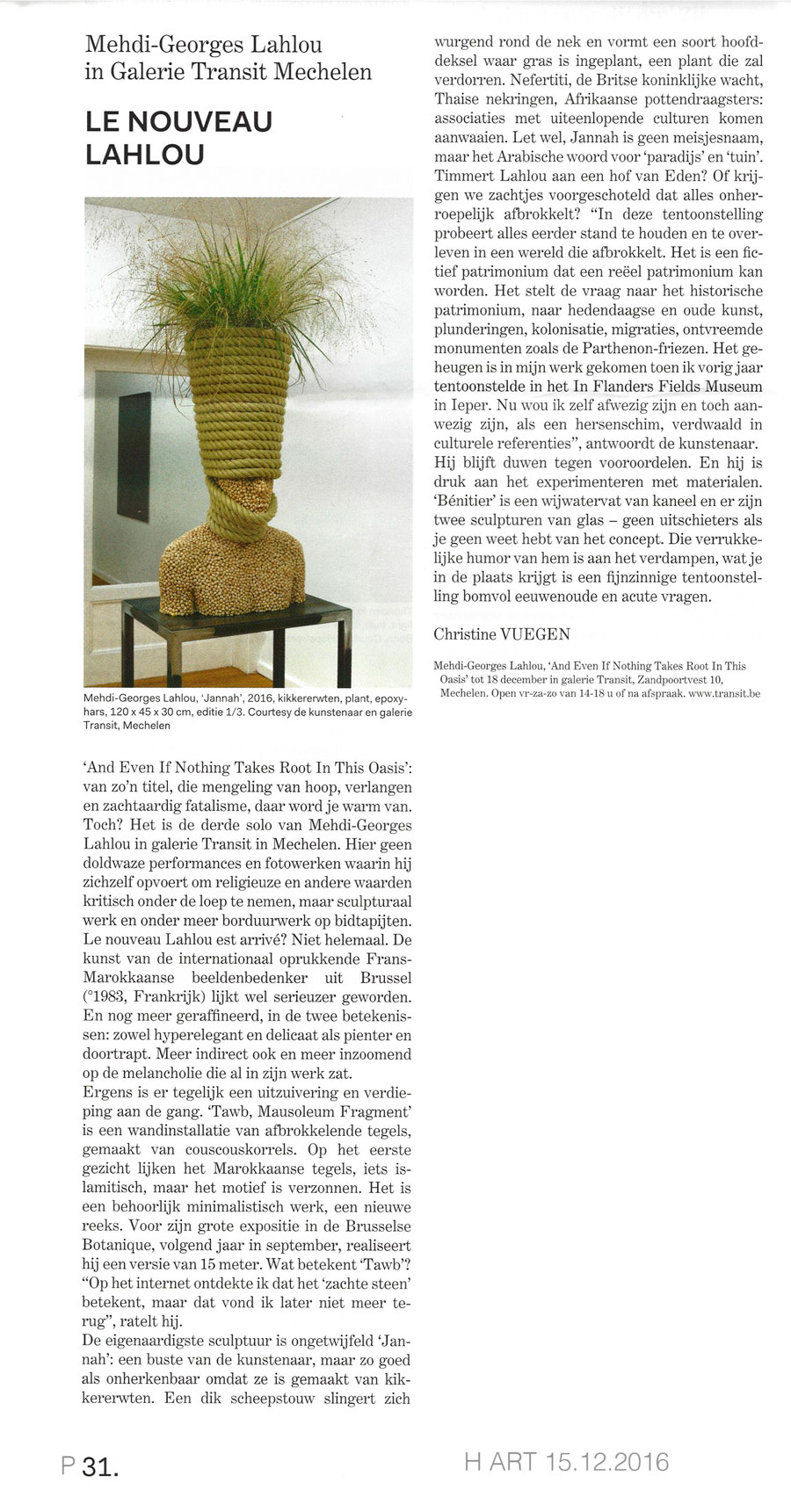

H ART artikel over tentoonstelling Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, 2016

Collect, december 2016

And Even If Nothing Takes Root In This Oasis

Klik op de foto om het artikel te lezen in het nederlands | Clickez ici pour le lire en francais

Artikel in Collect, december 2016, in het nederlands | Clickez ici pour l’article dans Collect,, decembre 2016, en francais

Read here the complete press release with the text of Sasha Pevak

The third solo exhibition of Mehdi-Georges Lahlou at Galerie Transit (Mechelen) “And Even If Nothing Take Root in this Oasis” invites to an imaginary pilgrimage across the relicts and the memories of some “orientalist” civilization. By juxtaposing the elements of diverse cultural contexts, the artist deconstructs the relationship between the so-called “Occident” and “Orient”, as geographical, cultural, and above all – mythical entities. Among the disintegrating heritage of an imagined past, we find ourselves in a lieu of paradoxes: a space without temporal, cultural or territorial landmarks that glides between reality and fiction.

Paradis Incertain, Centrale Box Brussels, 2014

| FRANCAIS | ENGLISH |

| Il y a un monde du paradis, un commerce du paradis, un rêve du paradis, un marketing du paradis. Chacun y va par un chemin pour le rejoindre. Certains s’isolent du monde, ils deviennent ermites, comme si s’extraire de ce monde d’ici-bas signifie rejoindre le paradis tant désiré. D’autres détruisent le monde comme si le paradis est au-delà des ruines, derrière les catastrophes, après le grand désastre. Cette liste pourrait être poursuivie à l’infini, tellement ce fantasme traverse les récits, les mythologies et surtout l’histoire de l’art.Il y a pourtant une vérité à avouer : le Paradis n’existe pas, non pas à cause de son absence, mais à cause de sa sur-présence dans les imaginaires. Et c’est bien de cette sur-présence que traite l’exposition de Mehdi-Georges Lahlou à la C-Box sous le titre Paradis Incertain.Ni extrait du monde, ni détruisant le monde, l’artiste rappelle dans son œuvre qu’il faut juste y revenir pour espérer un paradis réel. Celui de la matière, celui des sons, celui des odeurs, celui du flux des paroles, de l’interminable danse des rencontres à travers une terre globalisée. Alors, pour ce faire, il faut requestionner les images, les forcer à tourner le dos aux chimères.Dans cette exposition, le pari est risqué à double titre.D’abord, il y est question d’une seule œuvre au sens littéral du terme. On ne le dira jamais assez, tout artiste ne produit qu’une œuvre qu’il décline jusqu’à son dernier souffle. Lorsque Mehdi-Georges Lahlou m’a demandé d’assurer le commissariat de son exposition, je lui ai proposé de n’exposer qu’une seule de ses productions, une photo qui porte le titre : Paradis Incertain, 2013. Outre la « beauté » et l’extrême justesse de cette œuvre, elle est parmi les productions de l’artiste la seule où il tourne le dos – l’artiste est toujours le modèle de son œuvre. La figure flotte dans le noir et, on le suppose, regarde au plus loin de l’abîme sans jamais donner un seul espoir de révéler ce qui est vu. Le paradis est aussi incertain que caché.Ensuite, il sera question d’une œuvre à l’heure « de sa reproductibilité technique »*. Une fois la photo placée au centre de l’espace, elle se reproduira à saturation des cimaises. Une perte de l’aura ? Sûrement pas. La cohabitation, dans le même espace, et de l’œuvre et de ses reproductions, est une tentative pour restaurer l’aura de l’œuvre. Il est question de déployer sa polysémie et d’affirmer, ou du moins souligner, que le rêve de l’unicité est en passe de disparaître.L’exposition donnera � voir, dans une mise en scène de l’artiste, l’image d’une humanité en attente de paradis. Des êtres qui tournent le dos au monde ou aux chimères, mais tous regardent au loin l’absence de ce rêve tant attendu. On y attendra peut-être qu’ils se retournent, mais c’est bien là que l’œuvre s’arrête pour que le réel commence.Abdelkader DAMANI Commissaire de l’exposition* Walter Benjamin, L’œuvre d’art à l’époque de sa reproductibilité technique, in Œuvre III, Paris, Folio essais, 2000 | There is a paradise world, a paradise trade, a dream of paradise, paradise marketing. Everyone takes a path to attain it. Some cut themselves off from the world, become hermits, as if removing themselves from this earthly world means attaining that longed-for paradise. Others destroy the world, as if paradise is beyond the ruins, behind the tragedies, in the wake of the great disaster. The list could go on and on; because this fantasy is a recurring theme in so many stories and myths, and especially the history of art.Yet there is a truth that should be told: paradise does not exist, not because of its absence, but because of its excessive presence in our imaginations. And it is precisely this excessive presence that is examined in Mehdi-Georges Lahlou’s exhibition at the C-Box entitled Paradis Incertain (Uncertain Paradise).Neither removed from the world, nor destroying the world, the artist suggests, in his work, that it is just a matter of coming back to it to hope for a real paradise: that of matter, of sounds, of odours, of flowing words, of a never-ending dance of encounters across a global Earth. To achieve this, one must re-examine images, force them to turn their backs on the wild fantasies.In this exhibition, the artist takes a risky gamble on two scores.First, there is the issue of a single work, in the literal sense of the word. It’s been said before, but it bears repeating: artists only produce one work which they represent in a variety of forms throughout their lifetime. When Mehdi-Georges Lahlou asked me to act as curator for his exhibition, I suggested he presents just one of his works, a photo entitled Paradis Incertain, 2013 (Uncertain Paradise). Other than the ‘beauty’ of the extreme precision of this work, it is the only work by the artist in which he has his back to the observer – the artist is always the model in his work. The figure floats in the darkness and, we assume, is looking into the farthest depths of the abyss, without giving any hope of revealing what it sees. Paradise is as uncertain as it is hidden.Then, there is the issue of a work in its hour of « mechanical reproduction »*. Once the photo has been placed in the centre of the space, it will be reproduced, filling the picture rails. Does it lose its aura? Certainly not. Placing the work and its reproductions together in the same space is an attempt at restoring the work’s aura. It aims to deploy its polysemy and assert, or at least point out, that the dream of uniqueness is fading.The exhibition presents, in an arrangement by the artist, the image of a humanity awaiting paradise. Humans who turn their backs on the world or on fantasies, but all of whom gaze out at the absence of this much-awaited dream. One may wait until they turn around, but that is precisely where the work stops and the reality begins. Abdelkader Damani, curator* Walter Benjamin, L’œuvre d’art à l’époque de sa reproductibilité technique, in Œuvre III, Paris, Folio essais, 2000 |

2012

Portrait. L’homme aux talons aiguilles | 13 decembre 2012| Telquel online

Blouin Art Info 12 decembre 2012

RTBf Le grand Mag 17/10/2012-Speciale Daba Maroc : Medhi-Georges Lahlou

Le Soir sur Walking to Lahloutopia

Tele Bruxelles sur DABA Maroc

HOY Espana: Mehdi-Georges Lahlou: sin pelos en su objetivo

Reportage TV: TV/Focus/Tombe-du-ciel/Quand-l-art-contemporain-bouscule-les-religions, 2012

Avant 2012

| FRANCAIS | ENGLISH | NEDERLANDS |

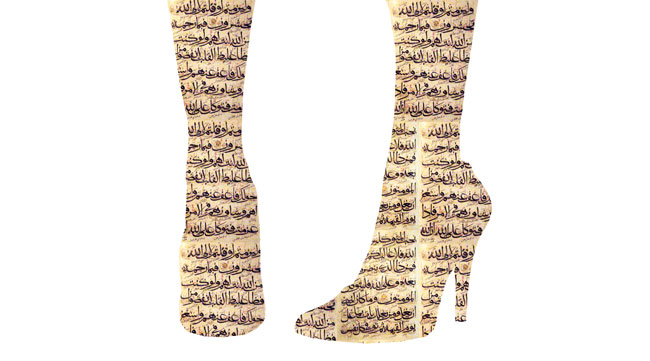

| Mehdi-Georges Lahlou was on the scenes of contemporary dance (with Maria La Ribot (E) The Company Le Douaré (FR), etc.) before been enrolling at the Beaux-Arts school in Quimper and after in Nantes (Fr). There he was passionate by performance art and video. Inspired by artists like Journiac, Molinier, Bowery, Viola, Neshat, Pane or Abramovic. He developed a poetic work on the identity, through imagery burlesque, combining travestissement and chimeric characters who parade to better hide their internal nil. Based in Brussels, Surrealism ground, he doesn’t stop talking about his own identities for better explore those of the others.Mehdi-Georges specifies the guidelines of his work, puting in question the representation, and the place of a body, or sexual body in Muslim cultures.He creates images where is confronted a double or a triple stigmas, through, among other, with the exhaustion of a fetish, for example, this of the high heel red shoes. He confronted it, as well, to the Cobblestones of our cities (the pavement of early streets), to objects, and as religious symbols.In his Art Works, as paintings, installations, objects, photographs…, Lahlou tries to find bridges, utopian, but humorous between North and South. What is an impossible synthesis. | Mehdi-Georges Lahlou était sur les scènes de danse contemporaine (collaboration avec Maria La Ribot (E), la compagnie Le Douaré (FR),etc ) avant de s’inscrire aux Beaux-Arts (Quimper, puis Nantes) Il s’y passionne pour l’art de la performance et de la vidéo. Inspiré par des artistes comme Journiac, Molinier, Bowery, Viola, Neshat, Pane ou encore Abramovic. Il développe un travail poétique sur l’Identité à travers une imagerie burlesque mêlant travestissement et personnages chimériques qui paradent pour mieux masquer leur néant intérieur. Installé à Bruxelles, terreau du surréalisme, Mehdi-Georges ne cesse de parler de ses propres Identités pour mieux explorer celles des autres. Il précise les orientations de son travail, questionnant la représentation et la place d’un corps, ou corps sexuel, dans les cultures musulmanes. Il crée des images où se confrontent un double, voire un triple stigmate. À travers entre autres, l’épuisement d’un fétiche, celui de l’escarpin rouge, qu’il confronte tout autant aux pavés de nos villes qu’aux objets et symboles religieux. Dans son travail plastique, peintures, objets, installations…, Mehdi-Georges tend à trouver des passerelles, utopiques, mais humoristiques entre Nord et Sud. Il s’agit d’une impossible synthèse. | E. Bouvard [korte tekst]:De performances en installaties van Mehdi-Georges Lahlou nemen de problematiek van culturele en genderidentiteit op de korrel, op een zodanig humoristische manier dat ze in elkaar vervloeien. In tegenstelling tot de biologische sekse, is genderidentiteit een sociale conventie, en wordt ze beïnvloed door de cultuur waarin ze ontstaat, welke dat ook moge zijn. Lahlou jongleert met verschillende gemeenschappen, etnieën en gendervariaties en ondergraaft bestaande conventies door zijn burleske acties. Hij maakt een typologie van de clichés over de Arabo-islamitische wereld en valt ze aan, middels rode naaldhakken, tijdens zijn performances die ook sportieve evenementen zijn, erop gericht om zijn viriliteit te testen. De naaldhakken zijn hier het symbool van de homo, de transseksueel en de travestiet. Het ‘hoofd van een Arabier’ van de foto draagt de schoenen van een vamp: stigma + stigma= 0.Mehdi-Georges Lahlou stelt de definitie van mannelijkheid in de islamitische cultuur in vraag. In elk van zijn performances test hij onophoudelijk hoe die cultuur aan het wankelen wordt gebracht, hier bij ons zowel als in Noord-Afrika, door het neerhalen van de geslachtsbarrières. Hij droomt dat de ‘tegengestelden’ zich verzoenen en dat er geen einde meer komt aan het Wonder(baarlijke). |

| E. Bouvard [court texte]:Mehdi-Georges Lahlou réalise des performances et des installations qui traitent avec humour à la fois des identités culturelles et de genre, au point de les dissoudre les unes dans les autres. En effet, si le genre est une construction sociale, par opposition au sexe biologique, il est alors pris dans le tissu culturel dans lequel il se construit, quel qu’il en soit. Jonglant d’une communauté à l’autre, de l’ethnie au genre, par ses actions burlesques, Lahlou effectue un travail de sape. Il se livre à une sorte de typologie des clichés associés au monde arabo-musulman, et les attaque à coup de talons aiguilles rouges, au cours de performances qui sont autant d’exploits sportifs sensés tester la testostérone. Ces talons sont ceux de la figure topique qu’est le queer, le trans ou le travesti. La «tête d’arabe» de la photo rencontre les chaussures de vamp: stigmate + stigmate = 0. Mehdi-Georges Lahlou s’attaque à la définition de la masculinité dans cette sphère culturelle, et teste en quelque sorte inlassablement, performance après performance, l’ébranlement de cette culture, ici ou là-bas, par la déconstruction du genre, rêvant une réconciliation des «contraires» et que le Merveilleux ne soit plus révolu. | E. Bouvard [short text]:Mehdi -Georges Lahlou produces performances and installations that deal with humour both cultural identities and “gender”, to the point of dissolving the one in the other. And indeed, if gender is socially constructed, as opposed to biological sex, then it is caught in the cultural fabric in which it is built whatever it is. Juggling from one community to another, from the ethnicity to the ‘gender’, by its burlesque actions, Lahlou makes an undermined work. He is engaged in a kind of typology of clichés associated with Arabian- Muslim world, and attacks it with knocks of red stiletto heels, during performances, which are all sports achievements supposed to challenge testosterone. These high-heeled shoes are those of the topical figure of what the queer, the transsexual or the transvestite is. The «Arab head» of the photograph meets the vamp shoes: stigma + stigma = 0 Mehdi-Georges Lahlou tackles the definition of masculinity in the cultural sphere, and, he tests, somehow tirelessly, performance after performance, the shaking of this culture, here and there, by the deconstruction of the ‘genre’, dreaming of a reconciliation of the ‘contraries’. | |

| Textes en Francais:EMILIE BOUVARD: Mehdi-Georges Lahlou [texte longue]Radio Judaica, 2010Pierre Giquel, 2010, chansonJuan Dario Gomez, PrefNag, Janvier 2011, pdf 1,4 MBRoxana Traiste dans Photograhie.comClaude Lorent dans La Libre Belgique 12.06.2012ArtPress Auot/Sept/Oct 2012, nr 392 | Texts in English:FREDERIC HERBIN: INTERVIEW WITH MEHDI-GEORGES LAHLOUEMILIE BOUVARD: OF STUPIDITY, GENDER AND ISLAM [long text]RADIO JUDAICA, 2010 |

For a text in German, please scroll down.

ArtPress Auot/Sept/Oct 2012, nr 392

It’s more sexy

Also of mixed race, performer, sculptor, video artist and photographer Mehdi-Georges Lahlou is the son of a Moroccan Muslim father and a Spanish Catholic mother. Riskily, and to great effect, he takes on his double culture as he weaves in and out of realities and constantly questions religious and sexual identity.

Working on the image and in the burlesque tradition of “idiocy” explored by Jean-Yves Jouannais. He claims the status of “falseness” for his photographs, staged scenes featuring himself that he reworked on Photoshop. Witness the series with Virgin and Child, a selection of Italian and Flemish Old Master paintings onto which Lahlou sticks a geometrical motif that is found widely in Casablanca. The title, It’s more sexy, thumbs its nose at fundamentalists of every stripe.

In his performances he dresses up as a woman, teetering on red high heels, which function as his feminine signature, while keeping the outward signs of his virility (body hair, beard). In his Stupidités controlees, which mock the “martyrdom” of certain pieces of performance art based on physical and mental endurance, Lahlou walks from the Eiffel Tower to the Centquatre, an art space in distant north-east Paris, in stilettos that, for any normally constituted woman, are torture. In Venice he held a huge watermelon in his mouth as long as he was physically able, until his jaws began to seize up and he choked. He peeled 65 kg of potatoes—his own weight—over a period of two and a half hours, cutting his hands at this absurd task. But Lahlou may also jump about like a child, dance the flamenco, belly-dance like an Oriental woman. He plays the bride, does a striptease backwards. The performances are fun, amusing, yet eloquent about the suffering of women, especially Arab women.

As a photographer, he is an obsessive self-portrayer. Almost always veiled by his niqab, he appears in images whose square format echoes the Kaaba, that great architectural cube around which the Muslim pilgrims process when they reach Mecca.

Vive la fêteis Lahlou’s ironic title for a high-angle shot down onto the huge crowd of the faithful, above which the artist mischievously hangs disco balls of the kind used in nightclubs. But Christianity gets just as much mockery as Islam. In Tango, Lahlou revisits the Descent from the Cross. His narcissistic Christ is carried in a very choreographic movement by a Mater dolorosaincongruously dressed in a niqab.

Lahlou does not judge. Rather, his work is about reclaiming a space of freedom and tolerance. Above all, he wants to avoid being pigeonholed—being put in that box which appears in many of his photos, as a metaphor of confinement, intolerance and fanaticism.

Two sculptures are particularly powerful in this respect. One is a bust of his own body, in plaster and fabric, with a stone balancing on his head. The stone brings to mind both the horror of stoning and Christ’s famous words to Peter: “You are Peter, on this rock shall I build my church”

In Sans titre, Paradise we have a prayer mat traditionally facing towards Mecca, on which Lahlou has placed wax casts of his hands and feet, as if he were kneeling and praying to Allah. The effect if very powerful: his body seems to be literally “melting” into the prayer.

An earlier exhibition by Mehdi-Georges Lahlou was cleverly titled Les Talons d’Allah(Allah’s Heels/The Yardstick of Allah). Elegantly using idiocy, the constant transgression of genres and frontiers of all kinds, he may well be achieving more in the fight against tolerance than a whole host of the right-thinking.

FREDERIC HERBIN: INTERVIEW WITH MEHDI-GEORGES LAHLOU

CONDUCTED BY EMAIL BETWEEN JANUARY 28 AND MARCH 5, 2010

Frédéric Herbin : I saw your work for the first time at the 2009 Youth Creation fair. For this occasion, you walked the whole 8 kilometers between the Eiffel Tower and the 104 exhibition hall, where the fair was held, on red high-heeled shoes. Several videos also pictured you wearing customarily feminine accessories : a scarf and, once again, your high-heels while stepping on an islamic praying mat. This being said, you always show up wearing a thick beard and sporting an eminently manly body hair display. How did this question of sexual ambiguity come up in your work and why are you so interested about it ?

MGL: Ambiguity… I’m almost the incarnation of it. More seriously, I’ve always been very passionate about the works of women artists, many of them are feminists, approaching matters of gender and sexual identity, such as Rosler, Export, Pane, to name a few. It is also in that purpose that I started questioning my own identity. At the beginning, the obvious way to deconstruct the male gender was through cross-dressing. It was, for me, a way to take possession of social marksthat weren’t mine.

But I also realized that cross-dressing was basically all about disguising yourself, strutting and flaunting it, and that – while the sex might be questioned – it remains crucially the same. This “burlesque” cross-dressing shakes up the idea of the male, but doesn’t transform the male into female. Keeping blatant male attributes for me seems necessary to make this ambiguity clear, be it social as much as sexual.

Then, I questioned myself on the definition of cross-dressing. Is it necessary to flaunt attributes of the other gender to be considered a transvestite. Indeed, a gesture, an action, an object, a feature belonging to the other gender (by that, I mean a social as well as a sexual gender), leads in the end to the same transformation of the body language that cross-dressing does.

In my work, I insist on showing the transformation by dressing up but also by acting up, which stresses the ambiguity (sexually and socially speaking). I’ve been using these very same red high heels for 4 years now. I though, at first, of several distinctive features to sport during my performances. First it was a wig, but I found it too explicit and not feminine enough (Warhol, Journiac, Sorbelli…). These shoes seemed just perfect, for their shape, their color and how they simultaneously stand out as glamour, feminine, fetishist, but also a transexual, transvestite, prostitute or fantasy-related object. Through this ambiguity, I also like to stress the paradox of me, a typically classified Arabic man, wearing such accessory. An Arab on one hand, red high heels on the other, stereotype + stereotype = null ?

F.H. : Indeed, your physical appearance – this time without resorting to any piece of clothing – identifies you as an Arab or as descending from arab origins. But, although you could be absolutely indifferent to it, you intentionally maintain in your artistic display (geometrical decorative patterns, veil, traditional arabic food, mats, hat and praying position…) some references to symbols customarily attached to the arabic-islamic culture. Is it for you as much – or more – a concern of yours than that of the gender ? You seem to be saying that the latter is even more complicated when it is confronted with an ethnic, religious-oriented representation. How do these two ideas connect ?

MGL : The representation of symbols associated to the Islamic religion is, today, a very delicate matter. Even if the modern flow of images, particularly the advertising ones, is quite accepted in countries like Morocco. The use and defamation of the religious aesthetics are forbidden. This is one of the reasons why my work can give rise to incomprehension or scandal. Indeed, derision, association, representation, parody… of the islamic symbols is a crucial thematic in my work. The muslim countries barely know, among themselves, any reflection on that matter. For that particular reason, I try to discuss, in my work, whether there’s an urge or not to reflect on such issues in that culture. If so, would the western theories, generally brought up by the feminists, be right ? Let’s not forget that homosexuality and other so-called deviant sexualities remain forbidden and repressed in islamic societies and ideologies. The notion of sex among society is the most perilous subject of the new modern islamic societies. One could even forget the great open-mindedness of the arabic-andalusian period, often referred to nostalgically in the arabic-moroccan literature.

Part of my work aims at analyzing the association of several issues and stereotypes that go along. Humor, gender, art and critique do not cohabit well with Mohammedan traditions. It is usually an impossible synthesis. When I use my own image, clearly associated to a specific culture, I obviously question the association that might be drawn from it. Islam is a community, which cancels out the individual in aid of social unity. The individual is modeled after and for the purpose of the group. Marginality, originality are generally not common knowledge in these societies. What my work precisely puts in light is the ability or incapacity of being different. For instance, when I perform outdoors, to be identified as an arab is crucial, and doesn’t just end at the state of the gender, it also addresses the ethnic definition of the gender. Would that performance have been made by an european artist, it would not have had the same social impact. I often have to face islamic communities in my journeys. And as my physical appearance clearly sets me as a member of their social group, the identification is immediate and allows me to directly question their own sexuality. I also raise the question of ethnic and religious assimilation. Is my body that of an Arab or of a muslim, or is it just about appearances ?

F.H. : By playing on these various social norms, you lay the finger on sensible issues. With the several controversies and debates rising up in Europe about Islamic-related symbols, one can sense a certain tension accumulating around religious identities. Your work has also been the target of a media frenzy when your installment “Cocktail or self-portrait in society” attracted acts of vandalism in Brussels. Do you set yourself limits ?

MGL : In most of the debates I participated in, I often spoke of the “self-censure” the artist imposes himself, words for which I have often been criticized. But I always say that in my case, this self-censure is a positive thing and is – sometimes – necessary to accomplish my work, attain my “goals”. Indeed, it helps me to attain sobriety and, sometimes, to focus my own intentions when they seem too strong or too direct. Which allows me to remain naturally genuine and humoristic. I don’t go after scandal. But knowing that tough issues are gonna be brought up, I try, in my creative process, to analyze how scandal may arise.

In my installment Cocktail or self-portrait in society, for instance, those red shiny heels, simply put down on an islamic praying mat, drew incomprehension from part of the, let it be said, orthodox muslims. Still, the “representation” inherently addresses the notions of “false” and “fiction”. It was an image ripped from the imaginary spectrum, not reality. Regarding scandal, it’s interesting to see why it’s forbidden, forbidden to do this, or that, to lay red high heels shoes on a praying mat… Who blessed that mat for it to become a property of Islam ? Who forbids, where is it written… This questioning is of course applicable to any obligation or prohibition established by Islam.

My work also conveys a social connection with the person it interacts with, questioning, notably, what is allowed and what isn’t. I question the “evil” that is transgression, divergence and deviance. What might be perceived as a political or social statement, or merely as an engaged cause, is nothing more than the materialization of my imagination which, because it tackles those prohibited things, creates a collective political and artistic debate. But at that time, the work of art, in its social aspect, doesn’t belong to me anymore, it becomes part of the group.

EMILIE BOUVARD: OF STUPIDITY, GENDER AND ISLAM

APRIL 2010

Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, teetering on his shiny red high heels, is walking on eggshells, and occasionnally breaking some a…., fraying some scarves and mats. Performer, more or less of a painter, “installer”, undoubtedly a video maker, he manages to build a coherent approach, swinging between the perilous abysses of stereotypes of the sexual gender, and the difficulty to come up with a strong and unbiased line about islam as an identity. How can one mess around again with the gender when it seems that Judith Butler said it all, how can one question the religious when the mere fact to represent it, and thus to recreate and interpret can create dissension ? Can you aim right ? Irritate without laxity ? The work of Mehdi-Georges is comparable to his high heels : ostensive and even blatant, eye-catching, he also has style, a certain ounce of chic in the ridicule he portrays, and knows how to keep the line.

This commitment in the ridicule and the efficiency of his work lays in the fact that Mehdi-Georges Lahlou confronts these two thematics, that of the gender and of cultural and religious identity. However, these two questions are inherently full of conflict, from the biological innate sex on one hand to the vested gender on the other, built individually and socially, and conflict also between culture and religion. The resulting work lies on four different facets, which allows for numerous associations between masculinity, femininity, islam as a religion and as a social-cultural factor. The work of Lahlou seems to constantly, methodically and somehow humoristically dig into the tensional zones where these thematics collide, especially by performing, video making and photographing. He subsequently puts himself in the lineage of artists who use performance to meditate upon genders and social norms, from Valie Export to Molinier, Neshat or Michel Journiac, yet by accumulating several thematics. Mehdi-Georges stresses the importance of feminist performances as they occurred in the 1970s.

Let’s take an example : in 2009, Mehdi-Georges Lahlou releases two works based on the islamic veil, This is not an islamic woman (16cm/25cm, digital printings on aluminum, 4 copies), a self-portrait of the veiled artist, and Undress me (video installment, 3mn36 loop segment), where once could watch him rigorously put on and off his veil, in the meantime : the video is edited backwards. And indeed, the man who puts the veil on and then off is a man, obviously arabic, hairy, fully-bearded, and whose inexpressive face isn’t devoid of a certain mischievous provocation. Therefore, the thematics at stake are dismissed : the victimization of the veiled Mohammedan woman is neutralized, the strong and traditionally fantasized perception of masculinity in the arabic world is directly linked to the former depiction of the veiled woman and is consequently foiled. Stereotype + stereotype = null. Everyone’s wrong, arabic-muslims and caucasians judeo-christians are all in the same bag. Under the veil, one man.

But what man ? The man with the face of an artist is in fact quite sporty : he accomplishes heroical feats, jumping hurdles, running, endlessly pilgriming around a black cubical object (resembling the Qa’abah), prays with piles of bricks on his back (Prayer – Al Fatiha, 30mn long performance, Brussels (BE), 2008). He’s a good craftsman : he can create traditional arabic decorative patterns (And by the roll?, acrylic and several other materials, 29x150x250cm, 2009), and moroccan dishes (Dar_koom, restauant, performance, 2010), displaying his sense of hospitality. But the meal is for one person at at time. The traditional patterns are made industrially “by the roll”, which knocks down the cliché of the moroccan craftsman, keeper of the traditions. And the heroical or religious acts are all performed either in a full body garment or naked, exclusively wearing the now famous shiny heels. The artist puts on a drag, and traditions are then wiped out.

What about cross-dressing ? To cross-dress is to change one’s identity by putting on a costume and modifying his or her general appearance. The word “transvestite” conveys a specifically sexual, gender-related idea of the body transformation. Cross-dressing is subversive in the way that, as Judith Butler put it in Trouble with the gender, it can put in doubt, question what seemed to be unquestionable et eternally definite – i.e. the essential categorization as either man or woman. By capillarity, and because the body is at the crossroads of the personal and the political, be it about the gender to any norm whatsoever, the transvestite implies the disruption of the whole social order, thus his social place of dropout and the perilous nature of it. But to be disturbing, the transvestite must remain in an unclear in-between : to drastically become someone else or adopt a “typically” (according to the social norms of where he lives) feminine or masculine behavior may seem on the contrary as a way to strengthen the stereotypes. This in-between, Mehdi-Georges Lahlou maintains it through collage ; he’s a man displaying obvious signs of masculinity : body hair, sex, muscles ; and wears women heels. He’s an ambiguous and disturbing object of desire. Here again, he multiplies the clichés : arabic man face + streetwalker shoes, stereotype + stereotype = null, nothing is viable anymore.

This is why his installement Cocktail or self-portrait in society (70cm/40cm, digital printings on aluminum, 4 copies, 2010) made of a set of praying mats in front of which were laid men shoes, except for one mat where were provocatively put the red heels, shocked and was attacked by partisans of a more traditionalistic islam. This, very simple, installment was disruptive in three ways :

- a woman does not pray among men in a mosque : cultural and religious thematic.

- what if this was not a woman ? a man does not wear high heels, unless he is not a man : thematic of masculinity in the arabic-muslim world, and elsewhere…

- one does not lay his feet on a praying mat : blasphemy of an evil agitator – or mere stupidity ?

Almost everything creates tension : the approach, the use of mockery, the omnipresence of the performer, three points which define the whole work of Mehdi-Georges Lahlou.

The set is that of the box : the box of the “restaurant” in which you get in, but also that of the installment inside, in which you cannot enter – it was the front window of the art gallery that was attacked in virtue of blasphemy. The box in which are trapped and played the videos. The box of Home Sweet Home (2009), the video that mocked a pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca, refers to the box which holds the Qa’abah around which Mehdi-Georges Lahlou walks endlessly, high heels to his feet, stepping on praying rugs. In Art Brussels, this box was laid on a steel platform, conveying ideas of imprisonment and harshness. These boxes refer to the confinement of the individual. They are directly related to the close-ups from the videos. Aesthetically speaking, the angles made from the rugs, the boxes all communicate : it conveys the idea of a culture that imprisons you. But these boxes are also monitors, frames, the frame of the images, imprisonment then becomes that of the clichés, the stigmatas. Lahlou opposes the cultural obligations, the weight of the traditions, the racial stereotypes and other commonly accepted clichés that this tradition conveys to other cultures. Getting out of a cultural frame is for Mehdi-Georges Lahlou to be confronted to another which shuts you in its turn. His work doesn’t deal much with the clash of the cultures rather than with the double imprisonment of multiple cultural identities.

Depressing ? Double-bind ? How to get out of the circle ? How not to give into madness ? One can act crazy and find a certain kind of “self”. Stupidity, which is a tradition in art, is a good way out and allows for thoughtlessness in a context often burdened with sense and strong thematics. Jean-Yves Jouannais in Stupidity, art, life, politics, method (Paris, ed. Beaux-Arts, 2003), names Breton and definies stupidity as a “distrust in theories and the dictatorship of the mind ; a contradiction leveled up to a haughty cultural language through a “modern recklessness” ; critique of the performance and its so-called renewal in spite of the depth of the artistic intentions”. One can then assume why Mehdi-Georges lives in Brussels, city stamped by the surrealism movement. Acting foolishly is going against seriousness, the heaviness of the religious systems – among others. Mehdi-Georges Lahlou is unstoppably burlesque, grotesque, foolish, stupid. His fit body, and his back obviously arched on his high heels, is inconveniently camped. In his series of videos named Controled stupidities (2009), Lahlou is eating a banana with the Quran laying on his head, or biting into a tennis ball, with a traditional headdress on. Ludicrous. How can such a madman create any real controversies ? When one is a religious extremist, or stands to defend a straight notion of masculinity, full of self-insurance, one does not want to argue with that kind of foolish character, which would mean losing one’s own dignity and reserve. And to look foolish in its turn. The recklessness of the foolish man allows for anything and goes past censure, without barely struggling.

Besides, if we still stick to Jouannais’ word, “‘stupid’ means simple, specific, unique. (…) Anything, anyone is therefore stupid as long as they only live for themselves.” One can then assume that there’s another outcome for that cat and mouse game and the mixing of the identities : being the clown, the fool who strongly expresses something still means stating something – no matter what -, that of a strong singularity, out of the box. The importance of the artist’s stature – Mehdi-Georges is an actor of all his performances – whose face appears from a video to another, from the first photo to the second, sometimes duplicated (Family portrait, 51cm/71cm, 4 aluminium printings, 4 copies, 2009), isn’t quite the sign of a narcissistic introspection, but implies the recurrent use of foolishness, in a comical purpose. For my part, I would be curious to see the young Lahlou digging further into that grotesque figure, and putting himself more at risk. And definitely toppling over to the Wonderful.

Mehdi-Georges Lahlou was born in Sables d’Olonne in 1983 and is French-Moroccan. He attended l’École Régionale des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (ERBAN), which he graduated from in 2007 ; he is currently pursuing a Masters at the St Joost Academy in Breda, Netherlands – and lives in Brussels. He exposed at Gallery M’atuvu (Brussels), and is now still present at Art Brussels in the Transit gallery (Mechelen) and at the Lille Art Fair, with the Xavier Ronse gallery.

EMILIE BOUVARD: Mehdi-Georges Lahlou

Mehdi-George Lahlou, perché sur ses talons aiguilles rouge vernis marche sur des oeufs, et au passage brise des c…, et effiloche quelques voiles et tapis. Performer, plus ou moins peintre, “installateur”, vidéaste à coup sûr, il parvient à construire une démarche cohérente, chaloupant entre ces dangereux récifs que sont les poncifs sur le genre (sexuel), et la difficulté à élaborer un discours distancié sur l’islam comme identité. Comment perturber à nouveau le genre quand il semble que Judith Butler a tout dit, comment interroger le religieux quand le simple fait de représenter, et donc de recomposer et d’interpréter peut poser problème ? comment toucher juste ? irriter sans facilité ? Le travail de Mehdi-Georges est comme ses talons haut : visible et même voyant, accrochant le regard, il a aussi du style, un certain chic dans le ridicule, et tient la route.

Cette tenue dans l’idiotie et l’efficacité de son travail tient au fait que Mehdi-Georges Lahlou croise ces deux problématiques, celle du genre et celle de l’identité culturelle et religieuse. Or ces deux questions sont elles-mêmes des lieux de tension, tension d’une part entre le sexe biologique inné et le genre acquis, construit individuellement et socialement, et tension d’autre part entre le culturel et le religieux. On arrive ainsi à une sorte de tableau à quatre entrées, qui permet de multiples combinaisons des pôles de masculinité et de féminité à l’islam comme religion et comme aire socio-culturelle. Les oeuvres de Lahlou semblent explorer avec constance, méthode et un certain sens comique, les points où ces tensions se heurtent, surtout par les biais de la performance, de la vidéo et de la photographie.

Prenons un exemple : en 2009, Mehdi-George Lahlou réalise deux travaux autour de la question du voile, Ceci n’est pas une femme musulmane (16cm/25cm, tirages numériques sur aluminium, 4 exemplaires), un autoportrait de l’artiste voilé, et Déshabillez moi (video installation, 03 minutes 36 en boucle), où l’on voit Mehdi-Georges se voiler et se dévoiler consciencieusement, avec une application qui fait sourire. Et en effet, l’être qui se voile, se dévoile et pose voilé est un homme, visiblement, de type arabe, poilu, barbu, et au visage dont l’inexpressivité n’est pas dépourvue d’une certaine malice provocatrice. Du coup, les discours topiques sont déjoués : évacuée la victimisation de la femme musulmane sous le voile et bousculée la masculinité virile et traditionnelle telle qu’elle se construit et est fantasmée dans le monde arabe – la voici transférée vers un autre motif topique qui s’en trouve du coup désactivé, celui de la femme voilée. cliché + cliché = 0. Tout le monde a tout faux, arabo-musulmans et judéo-chrétiens caucasiens se retrouvent dans le même sac. Sous le voile, un homme.

Mais quel homme ? Cet homme qui a le visage de l’artiste est un sportif : il réalise des exploits héroïques, saut de haies, course à pied, pèlerinages sans fin autour d’un cube noir (figurant la Qa’abah), fait ses prières avec des empilements de briques sur le dos (Prayer – Al Fatiha, Performance 30 minutes, Brussels (BE), 2008). C’est un bon artisan : il sait réaliser des motifs décoratifs arabes traditionnels (Et au rouleau ?, acrylique et divers matériaux, 29x150x250cm, 2009), et des plats marocains (Dar_koom, restaurant, performance, 2010), faisant preuve d’hospitalité. Mais le repas est pour une personne à la fois. Les motifs artisanaux sont faits “au rouleau” de façon industrielle, ce qui enfonce un coin dans le cliché touristique de l’artisan marocain gardien des traditions. Et les exploits et actes religieux sont réalisés en body et collants moulants, ou nu, avec au pieds les fameux hauts talons vernis. Les traditions sont travesties, comme le corps de l’artiste.

Il faut s’interroger sur le travestissement. Se travestir c’est changer d’identité par le biais du costume et de la modification en général de son apparence. Le terme de “travesti” renvoie plus spécifiquement à une modification d’ordre sexuel, de genre. La travestissement est subversif dans la mesure, comme le montre Judith Butler dans Trouble dans le genre, où il génère un doute, défixe ce qui semblait être fixée et stable de toute éternité – à savoir une essence masculine ou féminine. Par capillarité et parce que le corps est le champ de bataille où s’affrontent le personnel et le politique, du genre à l’ensemble des normes, le travesti suggère une perturbation de l’ordre social tout entier, d’où son statut de marginal et l’odeur de souffre et de dangerosité qui l’entourent. Mais pour être perturbant, le travesti doit rester dans un entre-deux trouble : devenir radicalement autre, adopter par exemple un comportement “typiquement” (selon les normes de la société où il vit) féminin ou masculin, peut apparaître au contraire comme un renforcement des stéréotypes. Cet entre-deux, Mehdi-Georges Lahlou le maintient par la juxtaposition ; il est homme et porte des marques traditionnelles de virilité : poils, sexe, muscles ; il chausse aussi des talons hauts – de femme. Il est un objet de désir double et troublant. Là encore, il cumule les stigmates : tête d’homme arabe + talons hauts de vamp, stigmate + stigmate = 0, plus rien ne tient et tout fout l’camp.

Ainsi, son installation Cocktail ou autoportrait en société (70cm/40cm, impression numérique sur aluminium, 4 exemplaires, 2010) composée d’un ensemble de tapis de prières devant lesquels sont déposés des chaussures d’hommes, à l’exception d’un tapis sur lequel crânent les escarpins rouge, a choqué et a été attaqué par des partisans d’un islam traditionnel. Cette installation, très simple, était triplement perturbante :

1 une femme ne prie pas parmi les hommes : question culturelle et religieuse.

2 et si ce n’était pas une femme ? un homme ne porte pas des talons hauts ou alors ce n’est pas un homme : question de la masculinité dans le monde arabo-musulman, et ailleurs…

3 on ne pose pas ses pieds sur le tapis de prière : le blasphème du provocateur – ou de l’idiot ?

Rien ne tient ou presque : une forme de cadrage, un usage de l’idiotie, et une omniprésence du performer, trois points qui caractérisent le travail plastique de Mehdi-Georges Lahlou de façon récurrente.

Le cadre est celui d’une boîte : la boîte du “restaurant” dans laquelle on entre, mais aussi celle de l’installation exposée, dans laquelle on n’entre pas – c’est bien la vitrine de la galerie qui a été visée par ceux qui criaient au blasphème. La boîte surtout dans laquelle sont enfermées et diffusées les vidéos. La boîte de Home Sweet Home (2009), cette vidéo qui parodie un pèlerinage à la Mecque, renvoie à la boîte qui en abyme dans la vidéo figure la Qa’abah autour de laquelle marche Mehdi-George Lahlou nu avec ses talons au pied, foulant des tapis de prière. A Art Brussels, cette boîte sera posée sur un socle en fer, évoquant encore davantage prison et rigidité. Ces boîtes figurent l’enfermement de l’individu. Elles correspondent à certains plans rapprochés des vidéos. D’un point de vue formel, les angles des tapis, des boîtes, se répondent : il est question alors d’une culture qui emprisonne. Mais ces boîtes sont aussi des moniteurs, des cadres, les cadres des images, et l’enfermement est alors celui des clichés et des discours, celui des stigmates. Lahlou renvoie dos à dos les obligations culturelles, le poids des traditions, et les cliches racistes et autres auxquels cette tradition donne lieu pour une autre culture. Sortir d’une culture, c’est pour Mehdi-Georges Lahlou être confronté à une autre qui vous y renferme à nouveau. Il n’est pas question ici du choc des cultures mais plutôt d’un double enfermement.

Déprimant ? Double-bind ? comment sortir du cercle ? et ne pas devenir fou ? on peut alors jouer au fou, et au passage trouver un genre de soi. L’idiotie, qui est une tradition en art, est une bonne porte de sortie et elle met de la légèreté dans un travail aux contenus lourds de sens et d’enjeux. Jean-Yves Jouannais dans L’idiotie, art, vie, politique, méthode (Paris, éd° Beaux-Arts, 2003), cite Breton et définit l’idiotie comme “défiance vis-à-vis de la thèse et de la dictature de l’esprit ; contradiction portée à la culture hautaine par “une gaieté moderne” ; critique des pirouettes de la forme et de leur prétendu renouvellement au détriment de la profondeur des pensées.” On comprend ici pourquoi Mehdi-Georges vit à Bruxelles, ville marquée par la surréalisme. Faire l’idiot, c’est lutter contre la gravité, et la lourdeur des systèmes religieux et autres. Mehdi-Georges Lahlou est en permanence burlesque, grotesque, ridicule, idiot. Son corps bien fait cambré sur talons hauts adopte des postures inconvenantes. Dans la série de vidéos Stupidités contrôlées (2009), Lahlou mange une banane le Coran sur la tête, ou tient dans sa bouche un balle de tennis, une coiffe traditionnelle sur le crâne. Débile. Comment un tel fou pourrait bien provoquer de sérieuses controverses ? Quand on est extrêmiste religieux, ou défenseur d’une masculinité straight et sûre d’elle-même, on ne croise pas le fer avec ce genre de joyeux drilles, ce serait au risque de perdre sa dignité et son quant-à-soi. Et d’être à son tour, ridicule. La légèreté de l’idiot fait tout passer et déjoue les censeurs, l’air de rien.

Et puis si on suit toujours Jouannais, “idiôtes, idiot, signifie simple, particulier, unique. (…) Toute chose, toute personne, sont ainsi idiotes dés lors qu’elles n’existent qu’en elles-mêmes.” Il est alors possible de suggérer qu’il y a là une autre sortie du jeu de miroir et d’emboîtage des identités : la position du clown, de l’idiot qui fait sans affirmer est une position malgré tout, celle d’une singularité maximale, sortie de sa boîte. L’importance de la figure de l’artiste – Mehdi-George est acteur de toutes ses performances – dont le visage apparaît de vidéo en vidéo, de photographie en photographie, parfois démultiplié (Portrait de famille, 51cm/71cm, 4 tirages sur aluminium, 4 exemplaires, 2009), n’est pas alors le signe d’une quête narcissique de soi, mais marque plutôt le retour de l’idiot, comme un gag récurrent. Pour ma part, je serais curieuse de voir le jeune Lahlou creuser encore cette figure grotesque, et la risquer davantage. Et basculer pour de bon du côté du Merveilleux.

Mehdi-George Lahlou est né aux Sables d’Olonne en 1983 et il est franco-marocain. Formé à l’Ecole Régionale des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (ERBAN), il obtient son diplôme en 2007 ; il poursuit actuellement un master à l’Académie St Joost à Breda – et vit à Bruxelles. Il a exposé à la galerie M’atuvu (Bruxelles), et est aujourd’hui présent à Art Brussels avec la galerie Transit (Mechelen) et sur Lille Art Fair avec la galerie Xavier Ronse.

Radio Judaica, 2010

Chers auditeurs, bonjour, vous êtes à l’écoute de l’émission Dialogue et Partage, produit par le collectif Dialogue et Partage.

En studio avec nous Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, artiste plasticien et Michel Grosse, sociologue, membre du collectif Dialogue et Partage et Stephane Goldsberg, professeur d’esthétique.

Le sujet de notre émission va être d’une manière un peu prétentieuse, un peu globale, l’art et sa liberté.

On va parler d’une œuvre que MGL, plasticien a exposé au centre Rogier. Je voudrais aussi préciser que MG vient de Nantes, il a été séduit par le surréalisme belge, il s’est installé à Bruxelles et il continue d’ailleurs un post-graduat en arts plastiques à Breda et il prépare des œuvres tout à fait remarquables. J’ai notamment vu une de ses installations située au 113, rue de Laeken, qu’il appelle des performances et dont nous parlerons aussi plus tard. Mais pour l’heure, ce qui nous amène c’est une œuvre qui a fait scandale, à la fois dans sa communauté et dans toutes les communautés religieuses conservatrices, pour ne pas dire orthodoxes, on va dire, et dont les journaux ont d’ailleurs fait étalage..alors de quoi s’agissait-il ? çà se passe au Centre Rogier, dans un des locaux,on a pu remarquer qu’il y avait un nouveau genre de mosquée, mais ceci n’est pas une mosquée, alors de quoi s’agit-il ? Il s’agit d’un ensemble de tapis de prière aux coloris tout à fait étonnants, très chatoyants, auprès desquels il ya des mocassins d’homme pour la plupart sauf sur un où il y a une fascinante paire de chaussures rouges. Alors MGL?

MG : Je voulais juste insister sur le fait que les mocassins d’homme sont devant les tapis et les chaussures de femme sont sur le tapis ce qui a justement causé pas mal de soucis..

Présentatrice: Alors le souci, c’est d’abord parce qu’il y a d’abord une paire de chaussures de femme rouge flamboyant au milieu de toutes ces chaussures d’homme et ensuite, elles sont sur le tapis.

Vous nous expliquez pourquoi c’est plus choquant quand c’est sur le tapis qu’à côté.

MG : A la base, j’ai misé sur l’esthétique parce que pour moi l’Esthétique amène justement une ambiguïté plus difficile à cerner du moins donc du coup c’est quelquechose qui relève de l’Esthétique, on va le voir comme une exposition, et tout d’un coup, on va se rendre compte qu’il y a quelque chose qui n’est pas normal et c’est là qu’il y a un problème.

Prés : Cette pièce a fait beaucoup de bruit et vous avez dû l’enlever.

MG : Exact .Les chaussures à talon sont sur le tapis alors que normalement on est censé ne rien mettre sur un tapis de prière. Celui-ci est le seul intermédiaire entre le prieur et le sacré, Allah, donc c’est comme une sorte de manque de respect que d’y mettre des chaussures qui sont censées marcher sur le sol.

P : C’est comme une provocation en somme.

MG : Exactement, provocation mais je ne l’ai pas cherchée à la base, elle est venue parce que parler de l’Islam, qu’on le critique ou pas, est pris comme une provocation et peut devenir un scandale. C’est vrai que les chaussures et toutes les choses qui sont censées être directement en contact avec le sol, ne peuvent pas être posées sur un tapis puisqu’elles ont été souillées. Un tapis de prière est censé garder le croyant propre et pur. Mais, j’ai fait le choix de les mettre sur le tapis directement, donc ces chaussures à talons me représentent, ce sont des chaussures que j’utilise dans de nombreux travaux et performances où je chausse les chaussures, je marche, je cours, je saute et au final, ces chaussures à talons sont comme un portrait de moi-même, c’est mon symbole.

Et donc, je savais qu’en exposant cette pièce en vitrine 24H/24 à la vue des passants, il y allait avoir scandale, mais c’est pour çà que j’ai fait le choix d’aller jusqu’au bout et utiliser cette symbolique en posan les chaussures sur le tapis. Qu’elles soient à côté ou sur le tapis, ça pose problème. Des chaussures de femme, qui plus est rouges à talon aiguille n’ont rien à faire dans une salle de prière, c’est un choix esthétique de les avoir mis dessus.

P : Et en fait, sur le plan religieux, strictement théologique, on va dire, est-ce que c’est quelquechose de tout à fait interdit..c’est la femme qui n’a pas le droit d’être présente en même temps que les hommes dans un lieu de prière, c’est l’homme qui n’a pas le droit de se faire passer pour une femme ?

MG : Il y a des règles dans une mosquée : les hommes s’installent d’abord tant qu’il y a de la place, et ensuite les femmes viennent.

P : Donc s’il n’y a pas de place, les femmes ne peuvent pas s’installer ?

MG : S’il n’y a pas de place , il y a une salle réservée aux femmes à l’étage, où les hommes ne peuvent pas aller.

Mais normalement, dans le Coran, il est bien précisé que la femme doit prier derrière les hommes, et s’il y a de la place derrière eux mais qu’elles décident quand même d’aller dans la salle réservée aux femmes, la prière peut être annulée parce qu’elle est vraiment censée être derrière l’homme en prière mais pas parmi..

P : Stephane Goldsberg, je me tourne vers vous pour que vous nous donniez quelques éléments à propos de l’attitude de la religion par rapport à la place de la femme au sein du monde de la prière, des lieux de prière et aussi par rapport aux travestissements de l’homme vers la femme que symbolise cette paire de chaussures au milieu des hommes . Comment çà se passe pour le judaïsme, d’une part mais aussi dans l’Islam et d’autres religions ?

SG : Pour préciser, il s’agit ici d’une œuvre d’art qui n’est pas un eoeuvre d’art religieuse, c’est un oeuvre d’art profane, donc qui n’est pas régie par les règles de l’art religieux musulman mais qui est une œuvre d’art qui touche un sujet éminemment religieux puisqu’il s’agit d’escarpins typiquement féminins, rouges sur un tapis de prière, orienté vers la Mecque le tout à la vue des passants d’un quartier du centre-ville, donc le statut de la femme dans les trois religions qui se réclament d’Abraham, Judaïsme, Christianisme et Islam est toujours différent. Dire s’il est soumis ou pas, c’est une question d’interprétation et je n’ai pas le dernier mot sur cette question mais la fonction de l’homme est toujours distincte de la fonction de la femme. Donc quelque soit la fonction qu’on donne à la femme, les mélanger, dissoudre cette opposition, c’est déjà bien entendu ébrécher la religion dans son fondement.

Alors, pour l’art justement, il faut savoir que dans les trois religions, il y a un interdit de l’image dans les trois religions-je dis bien- et dans les trois religions, il y a une pulsion humaine de fabriquer des images.

Dans le judaïsme et dans l’Islam, l’image massivement est interdite et n’est pas pratiquée, d’une manière graphique, figurative.

Dans le christianisme, çà dépend. Chez les catholiques, on s’en donne à cœur joie. Chez les orthodoxes, c’est extrêmement réglementé dans l’icône , chez les protestants, ils retournent un peu à l’Ancien Testament, et donc ils limitent bien entendu le nombre d’images.

Dans l’Islam, l’image est complètement bannie, ce qui ne veut pas dire que les musulmans n’ont pas de photos, pas d’images. Une maman musulmane même dans une ville disons très musulmane, pour faire vite, elle a la photo de ses enfants sur elle, dans sa poche, çà ne pose pas de problème mais la photo, dès qu’il s’agit du culte entre en contradiction.., donc on ne peut pas prier devant une image par exemple.

MG : Non parce que çà peut annuler la prière et déconcentrer le croyant. Le prophète a dit qu’il ne doit pas y avoir de représentation d’âme dans un endroit où l’on prie, pour ne pas être perturbé.

S : Ce ne sont pas les musulmans qui ont un problème en soi avec l’image, mais un problème/interdit avec l’image dans le lieu de prière ou bien si cela touche à la religion, or ici bien entendu des escarpins de femme sur un tapis de prière dans une salle réservée aux hommes, je ne sais pas pas si cela vise à choquer, mais la personne qui le voit comprend intuitivement, spontanément que cela vise à choquer .

MG : Plus qu’une volonté de choquer directement, je pose des questions, je raconte des histoires, je suis un peu comme un poète.

P : On sait que dans le temps, au 18ème, 19ème , les représentations féminines, érotiques ou sexualisées de la femme étaient tout à fait acceptées et même mises en valeur. Je pense aux miniatures indiennes, persannes. Par rapport à çà, on voit bien qu’il y a une forme de régression, de censure, aujourd’hui, d’une manière générale,bien sûr ici c’est lié à la prière, mais en général, on a tendance à vouloir couvrir la femme, ce qu’on ne faisait pas pour les mêmes raisons en tous cas, avant.

Michel Grosse : Je voulais demander quelle avait été au départ votre intention ? Vous aviez une proposition précise, un message précis ? Comment vous est venue l’idée en quelque sorte ?

MGL : Mon travail relève assez fortement de l’autobiographie. Je suis un des sujets principaux de mon travail, je suis entre deux cultures, une culture occidentale avec une mère espagnole et une autre musulmane avec mon père vivant au Maroc. Mon travail est aussi d’essayer de trouver d’impossibles synthèses entre les deux, c’est d’essayer de me positionner, essayer de savoir , de créer de nouvelles nostalgies si c’est possible, donc clairement j’utilise des symboliques qui me sont fortes, qui m’ont été données, parfois imposées mais légèrement, jamais on m’a forcé ou imposé. On ne force pas dans l’Islam, bien qu’on en ait envie parfois. L’esthétique musulmane est quelquechose qui m’interpelle, que j’ai choisi et que je mêle, encore une fois avec une esthétique occidentale là on voit clairement le jeu entre l’orient et l’occident.

Michel : Cela dit, vous saviez évidemment qu’il y avait un petit élément sacrilège parce que quelquepart vous touchez à un représentation sacrée, une représentation plus ou moins inscrite historiquement…donc vous touchez un peu les limites de ce qui est sacré, vous profanez, vous le saviez..

P : Mais il espérait être compris peut-être.

MGL : Oui j’espérais être compris, mais en même temps je savais aussi ne pas être compris parce que la pièce est quand même assez directe, on ne peut pas dire le contraire mais encore une fois, j’aime le burlesque, j’aime aussi faire rire les gens et c’est par ce biais-là que j’essaye de faire passer mes messages. Beaucoup de gens ont ri, voire même des musulmans aussi.

P : Donc ils ont compris l’aspect surréaliste de votre installation.

MG : Oui je pense, même s’il y a des groupes marginaux qui étaient complètement contre, qui ont craché, cassé la vitrine (ébréché). Il y avait des musulmans très heureux, qui ont parlé avec moi, me disant que c’était très beau. C’est surtout le mot qui revenait, c’est très beau. C’est justement par ce burlesque que j’essaye aussi de désacraliser le sacré pour questionner la sexualité, le travestissement, et mon corps dans ces différentes cultures.

Michel :La question qu’on pourrait se poser est de savoir ce qui est encore sacrilège aujourd’hui ? On recule indéfiniment ce qui est sacré, on essaye de détruire la limite, la frontière entre le sacré et le profane.

Stephane : Encore une chance qu’il n’y ait pas eu représentation de quelqu’un qui priait ou de la figure même du prophète ou de Dieu car çà, çà aurait été absolument une réaction violente extrêmement violente.

P : On n’a pas le droit de représenter la figure humaine ou bien on n’a pas le droit de prier près de la figure humaine ?

S : Ni l’un ni l’autre c’est-à-dire on ne prie dans les religions monothéistes, issues d’Abraham, on ne prie que Dieu, parfois dans certaines religions , disons le christianisme, une image permet de focaliser l’attention, disons de passer par le saint pour s’adresser à dieu mais comme dit le proverbe, il vaut mieux s’adresser à Dieu qu’à ses saints mais ni dans l’Islam ni dans les autres religions on ne prie une image ; maintenant l’Islam est particulièrement rigoureux sur les représentations.

P : Ce que je voulais demander, est-ce qu’on peut représenter la figure humaine dans le judaïsme ? Pendant longtemps, c’était considéré comme interdit.

S : La question est : est-ce que çà se fait dans le contexte sacré ou non. Aujourd’hui, un juif peintre, par exemple, j’en connais, çà ne pose pas de problème. Ils peuvent même représenter quelques scènes de tel ou tel rabbin discutant avec un autre. D’habitude ils ne sont pas d’accord.

Maintenant la figure de Dieu, çà reste interdit.

MGL : C’est aussi pour çà que j’ai insisté sur l’absence : les chaussures représentent les personnes qu’on imagine en prière, de là découle l’ambiguïté.

P : En fait c’est une paire de chaussures de femme mais qui signifie que parmi ces hommes il peut y avoir un homme qui lui, met des chaussures qui sont pas comme celles des hommes.

Donc, ce que vous revendiquez c’est de pouvoir être accepté éventuellement dans une mosquée, avec le choix vestimentaire ou extérieur que vous voulez.

MG : Moi, je revendique rien, je suis pas activiste, ni actionniste, je raconte des histoires. Je ne suis pas en train de réellement prendre position, je ne suis pas féministe.

P : Vous revendiquez pas , je veux dire, vous signifiez par là que les hommes peuvent aussi ressembler à des femmes finalement.

MG : Je questionne la possibilité du moins…C’est suggéré, je questionne la possibilité.

P : Il n’y a pas de fétichisme de chaussures derrière ?

MG : Faut demander à ma mère…(rires)

P : Cette œuvre, tous vos rapports à l’art posent tout de même le problème ancestral du rapport de l’art et de la liberté. A cet égard, je voudrais vous citer un petit évènement, une petite anecdote qui s’est produite quand Trotsky expulsé d’URSS a rencontré Breton qui rédigeait son Manifeste du Surréalisme et qui avait écrit « En Art, tout est permis, sauf ce qui est contre-révolutionnaire ». Trotsky qui revenait de l’enfer si on peut dire, qui savait ce que çà voulait dire être contre-révolutionnaire-n’oublions pas qu’on a fusillé des poètes pour leurs poèmes en URSS à cette époque- a fait barrer la 2ème partie de la phrase, il restait donc « En Art, tout est permis ».

Alors est-ce qu’on est aujourd’hui dans une société qui pratique cette tolérance-là. On a notamment vu avec les caricatures de Mahomet, au début du 20ème les impressionnistes ont quand même fait beaucoup de tableaux refusés(le fameux Déjeuner sur l’herbe, de Manet),

MGL : Pierre Molinier..

P : Des tas d’artistes proscrits ou des œuvres proscrites.

On a eu après une très grande phase de liberté surtout les vingt dernières années.

On est maintenant dans une phase, dirait-on de censure plus exacerbée et aussi de réaction extrêment vigoureuse par rapport aux expressions de liberté.

MGL : L’exposition « Présumé innocent » qui montrait pas mal de travaux d’artiste sur la sexualité de l’enfant. C’est une exposition qui a eu lieu à Bordeaux, les associations d’enfants ont protesté, porté plainte et maintenant les curateurs et le directeur du musée sont en procès depuis 2000, année du commencement de l’exposition. C’était pourtant des œuvres qui ont circulé partout, des œuvres d’Annette Messager, les artistes ont été poursuivis par la police jusque dans leurs ateliers.

Michel : Moi je dirais quand même que c’est vrai qu’on peut considérer qu’il y a ici et là des effets de censure, des fatwas surtout venant del’Islam ou d’autres, mais d’autre part le monde contemporain caractéristique par son éclectisme et sa diversité et donc ce que l’on constate aussi dans le domaine de l’art contemporain, c’est une tendance à la provocation, au scandale, parfois même un peu systématique. Je rappelle par exemple ce travail des frères Chapman qui reconstituent des minis camps de concentration, on a pu en voir à Venise ou par exemple le fait qu’ils ont racheté aux enchères les aquarelles d’Hitler, qui les ont retravaillées visuellement .. donc je veux dire qu’il y a de nombreux exemples dans ce domaine.

P : On touche à la Shoah qui est quand même quelquechose de particulier.

S : Oui je sais, nous sommes evidemment ici dans un autre registre mais quelquepart tous ces artistes essayent de jouer sur des limites et donc inévitablement sur une réaction, sur une réaction scandalisée quoi, c’est clair que c’est devenu une valeur en soi.

MG : Est-ce que le mot « scandale » est un terme artistisque ?

Je ne sais pas si une œuvre peut être scandaleuse, oui, elle l’est dans les faits.

P : Par rapport à la Shoah, petite parenthèse,la Shoah c’est quand même une mise à mort qui exprime la cruauté extrême dont l’humanité a été capable, par rapport à çà Dornaut disait c’est indicible, et donc aucune expression artistique peut rendre compte de çà. Chapmann met en scène quelquechose qui a une signification plus historique que véritablement artistique. C’est pas vraiment choquant, provocant ce qu’il fait, au contraire, tout est dans la manière dont est quand même mis en scène l’œuvre et mais alors quelles sont les limites, on va dire, Shoah excepté, est-ce qu’il faut imposer des limites à un artiste ? .L’art c’est quand même une manière de donner au monde une beauté ou du moins d’en faire découvrir la beauté ou de lui apporter une beauté.Est-ce qu’on est pour limiter ?

S : Pour la Shoah, evidemment c’est different puisqu’elle n’est pas arrivée partout mais prenons le cas de la Révélation qui est arrivée partout manifestement. Certes, on ne peut pas parler de maturité d’une religion, ce n’est pas un organisme qui murit , qui est jeune, même si une religion nait et parfois meurt, cela etant on ne peut pas aujourd’hui critiquer les différentes religions avec la même assurance il est quasiment banale de se moquer de certains hauts faits religieux, de certaines religions c’est presque enfoncé une porte ouverte aujourd’hui de se dire scandalisé par ce qui est arrivé lors de l’Inquisition, par exemple. C’est enfoncé une porte ouverte, puisque tout le monde en ce compris une grande partie de l’église est d’accord, l’église qui a fait amende honorable etc,maintenant dès qu’on touche à l’art profane ou sacré et qui touche en tous cas au sacré, il y a une formede censure, et une forme d’autocensure, c’est pour çà qu’il n’y apas autant d’artistes comme vous car moi si j’etais artiste,j’éviterais soigneusement ce sujet pour des raisons..pour pouvoir vivre le plus longtemps possible sans de trop grands problèmes.

MGL : Il y a la possibilité d’être catalogué comme un artiste à scandale. J’ai beaucoup de mes collègues qui se retirent de ce qui s’est passé autour de cette pièce-là, parce qu’ils ne veulent pas y être associés.

P : Alors que c’est la réaction. C’est vrai qu’on est dans des époques ou la critique des religions est mal vécue parce qu’on est sur un amalgame tout a fait terrible,c’est que evidemment on a le droit, même le devoir parce qu’on est des hommes et on pense de critiquer les religions mais on n’ est pas là pour critiquer les gens qui pratiquent cette religion. Il y a une différence entre critiquer l’islam et critiquer les musulmans et donc là on a un problème éthique et un malentendu terrible.

MG : Bien sûr mais en même temps encore une fois, je le redis la pièce relève de l’esthetique bien sûr. Mon but premier n’était pas vraiment de critiquer.

P :On a bien compris, vous êtes dans une expression de l’art où vous voulez aller le plus loin possible dans ce que vous avez envie d’exprimer. Mais malheureusement aujourd’hui, aller le plus loin possible, c’est dépasser une norme que les gens ne sont pas prêts à accepter.

MGL : Justement par rapport à l’auto-censure, pendant toutes mes études, je me suis demandé à qui j’allais montrer mon travail et çà a été un gros souci parce que j’avais des travaux que je faisais pour mon père (pour les musulmans), et des travaux que j’effectuais quand j’étais étudiant pour l’école. Plusieurs fois, je me suis demandé si je pouvais connecter les deux. Si je pouvais tout montrer ou choisir le public. Ici, c’est la première fois que j’ai pris position, je me suis dit là je vais vraiment montrer mon travail à des personnes aussi concernées par le sujet, du coup il y a eu des retours..

P : On pourrait dire que vous êtes un passeur et que vous avez envie à la fois d’amener le monde musulman vers une forme d’ouverture à une manière d’exprimer la beauté et le rapport au monde.

S : çà invite la société civile à se poser la question de l’éducation sur l’art des jeunes générations, si aujourd’hui, les jeunes sont choqués par ceci, çà veut dire que peut-être on n’a pas avancé beaucoup depuis le Manifeste du Surralisme..

MG : Et pourtant…

P : On a avancé et on a reculé mais avec des artistes comme Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, je pense qu’on est sur la bonne voie pour avancer à nouveau …

Merci à tous.

RADIO JUDAICA, 2010

Fellow listeners, hello, you’re listening to Dialogue et Partage, produced by the association of the same name.

In studio with us we have Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, visual artist and Michel Grosse, sociologist, member of the association Dialogue et Partage, and Stéphane Goldsberg, aesthetics professor.

The topic of our show today is, in a rather pompous and global way, art and its freedom.

We’ll discuss one of Mehdi-Georges Lahlou’s works, which was recently exhibited at the Rogier centre. I would also like to add that MG comes from Nantes, he was attracted to belgian surrealism, moved to Brussels and is now following a post-graduate degree in plastic arts in Breda. He’s the creator of a large number of quite remarkable pieces of art. I’ve seen one of his instalments located at the 113, rue de Laeken, which he calls performances and which we’ll discuss later. But for the time being, let’s address what brings us all together here. It’s a very controversial artwork, to its own community as well as to other radical religious communities, we could probably define them as ‘orthodox’, and which the press has already covered quite extensively. So what was it about ?

The artwork we’re talking about is an exhibition of several islamic praying mats, in very surprising and appealing color shades, next to which are laid down a pair of men’s moccasins. Except for one particular mat, next to which is a fascinating pair of red high heels.

So MGL ?

MGL : I just wanted to add that, while the mocassins are next to the mats, the pair of women heels is right on top of one. That was what generated so much controversy.

Host : So you’re saying the matter is, firstly, that the gaudy feminine shoes are displayed among the other men shoes and, secondly, that they’re on one of the very mats.

Can you tell us why it’s more shocking to have put them on it rather than to the side ?

MGL : Initially, I did it this way because I found aesthetically more interesting. To me, aesthetics imply a complex ambiguity. One goes to see an artwork such as this one, thinks to himself that this just another exhibition and, all of a sudden, he realizes something is off and is creating a problem.

Host : This show generated a lot of criticism. You had to withdraw it.

MGL : Indeed. The heels were on the rug where you’re usually supposed not to put anything. It is seen as the sole intermediate between the believer and the sacred, Allah, so it is kind of a lack of respect to put any shoes on it. They’re supposed to lay on the ground.

Host : This is sort of a provocation.

MGL : Absolutely, although I wasn’t looking for it at first. It came because talking about Islam, criticizing it or not, is considered a provocation and can easily become a scandal. It’s true the shoes and whatever is in direct contact to the ground isn’t supposed to be put on a rug whatsoever, for the simple fact that they’re soiled. A praying mat is supposed to keep the believer clean and pure. But, instead, I decided to put them directly on it. These high heels shoes represent me, these are shoes I use frequently in my work and performances where I walk, run, jump with those on. Those shoes are portrait of myself, this is my own symbol.

Therefore, I knew that by exhibiting them in the window 24/7, for every passer-by to see, there would be scandal at some point. But this is why I decided to go for it and use this symbol by putting on the mat. Be it next to the mat or right on it, it would be an issue. Women shoes, red high heels even, have nothing to do in a praying room, it was a visual and aesthetic choice of mine to have put them on it.

Host : On the religious aspect and strictly theologically, is this really the issue here ? Is it that women cannot be in the same praying room as men or that men cannot pretend to be women ?

MGL : In a mosq you have rules : men come in and sit first, while there’s still room. Only afterwards are women allowed in.

Host : So if there isn’t any room, women cannot get in ?

MGL : When there’s no room left, women are allowed in another specific room upstairs, where men themselves cannot go.

But in theory, as the Qu’ran says it, women have to pray behind men. And if they do decide to pray in the other room, on the floor above, the prayer can be called off by the Imam. She is forbidden to pray amongst men but customarily has to pray behind them.

Host : Stephane Goldsberg, what can you tell us about the religious stand towards women, the place they occupy amongst other followers, praying rooms and also the cross-dressing of men into women that these shoes symbolize ? How is it regarded in Judaism, in Islam and other religions ?

SG : For starters, this artwork we’re talking about is not a religious one, it is a profane one, which doesn’t answer to the dogma of the Islamic religious artistry. This is something which obviously addresses the sacred given that those typically feminine red heels are laid on the rug, all of them facing the direction of Mecca. The location of this show, right in the middle of a busy central area of the city, made it noticeable to any kind of passer-by, be they muslims, jews, christians. To any one of these people, the place of women in society and religion is different. I couldn’t say whether this place is submissive or not in some of these religions but I can clearly state that, in the eyes of any of these three confessions, the part men play is very distinct to that of women. So, whatever function you might want to give women, to mingle it with that of men is to dissolve that opposition, and so to crack the basic foundations of religion. In art precisely, there’s a clear notion of what’s forbidden in these three religions. Let it be said, there’s a strict limit to their imagery. This is in direct contraction to the humain urge to make and produce images.

In Judaism and Islam, imagery is mostly prohibited and is usually not executed in a graphic, figurative way.

In Christianism, things are different. Amongst catholics, it’s common practice. Amongst orthodox, this is extremely restricted. For protestants, given their return to the scriptures of the Old Testament, they’re slowing down massively on the amount of images produced.

In Islam, image is absolutely forbidden, which doesn’t mean though thay muslims themselves don’t have pictures, images. An islamic mother, even in a very let’s say radical townm carries around pictures of her children with her, in her pocket. Photography is in itself not a problem, except when it has to do with the religious beliefs. One cannot pray in front of a picture for instance.

MGL : No, because this can annul the prayer and distract the person praying. The prophet said there shouldn’t be any representation of soul in the praying area, in order for believers not to be distracted.

SG : Muslims themselves don’t have a problem with imagery, they do forbid on the other hand a pictural representation in a praying room. However in this case, women shoes on a praying mat in a room strictly supposed to be for men – I don’t know if it’s supposed to shock in any way but the person who sees it for the first time understands immediately, intuitively that this is a provocative move.

MGL : It’s more than just wanting to shock people, I’m raising questions, I’m telling stories, kind of like how poets do.

Host : We all know that in the past, during the 18th or 19th century, the erotical or sexual representation of women was widely accepted and even acclaimed. I’m thinking of indian miniatures or the persian ones. Nowadays, we can clearly see that there’s a decline, a censorship for such graphic representations. Generally speaking, of course here we’re talking about praying, but in general, there’s a tendancy to cover women, which isn’t done today for the same reasons as it was before.

Michel Grosse : I wanted to ask you what was your initial intention ? Did you have a precise message to convey ? How did you get that idea ?