Nikita Kadan | Children Are Surrounded by Art

& Yevgen Nikiforov | photographs

| English | Nederlands |

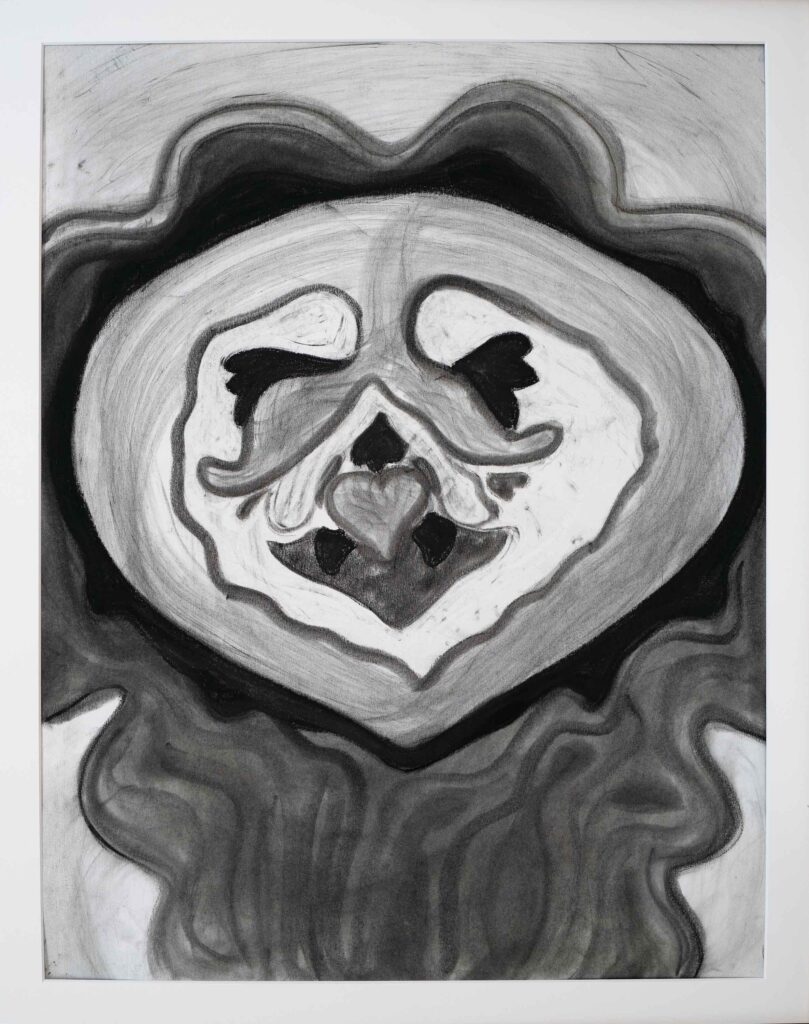

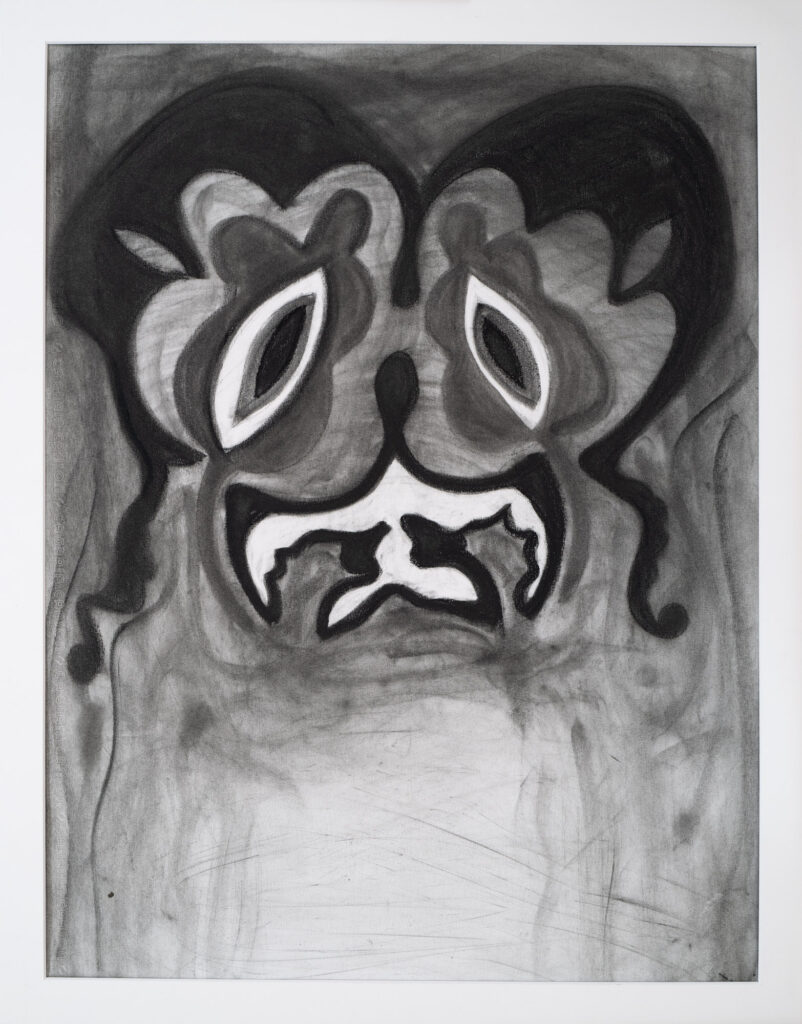

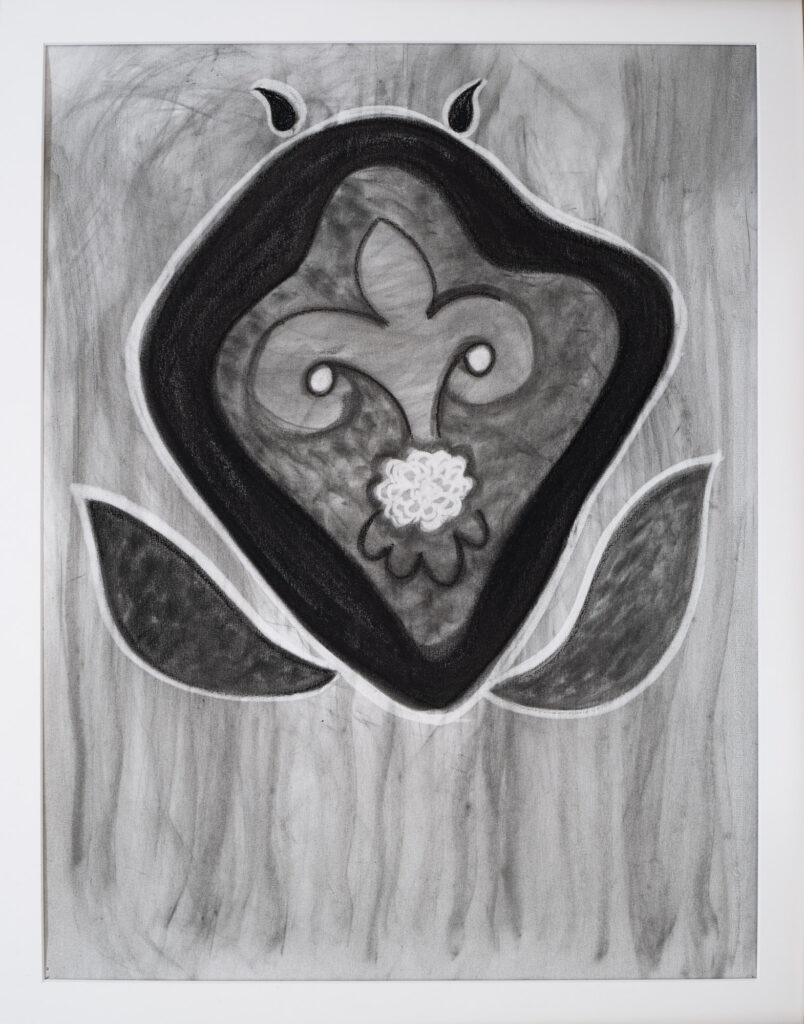

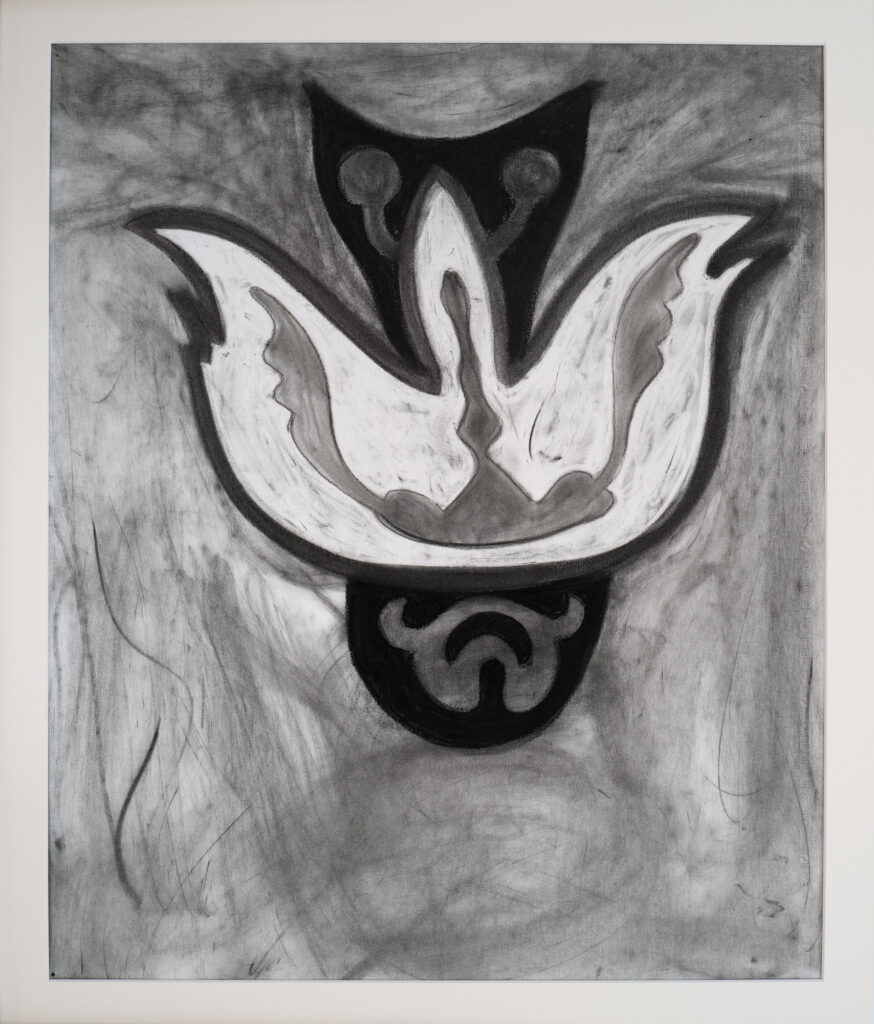

| For his fourth exhibition in gallery Transit, Nikita Kadan [* 1982] chose to go back to an experience that he had as a child, but which took a completely different turn later in his adolescence, then as a young adult and now in 2021. The communist palaces for children and youth, richly decorated with mosaics, seem to be an important heritage only now, when nationalists want to tear them down and young people organize rave parties in them. Kadan also invited the photographer Yevgen Nikiforov [* 1986] for this project, who beautifully portrays this Ukrainian architecture from the 60s-80s. “Children Are Surrounded by Art” is a 1970s brochure about sanatoriums, pioneer palaces, children’s recreation camps and the monumental art that adorned them. On its pages I found many photographs of children’s camps in Crimea – neo-modernist structures on the Black Sea coast, as well as Ukrainian Soviet decorative art, which is being actively destroyed today as part of the “policy of decommunization”. The Russian annexation of Crimea and Ukrainian state anti-communism threw their reflections on archival images, making the latter something completely different from what they were before 2014. Each image lives in time and changes with it. These changes are dictated by political history – one and the same picture in a short time can be in the area of encouraged, denied and ignored. However, there is also a story of our sensitivity, an emotional story. The huge semi-dark halls of the Soviet palaces of children’s creativity were for me as a child in the 1980s an image of boredom, empty time. For me as a teenager in the 1990s, it was an anxious and inviting space of abandonment and uncontrollability, freedom as a uselessness to anyone. In the 2000s, these halls were built up with plastic kiosks and covered with advertising banners, becoming the embodiment of the “eternal today” of victorious peripheral capitalism, devoid of historical dimension (this is how I found them when I became an artist). In the 2010-20s, these gradually crumbling, decrepit, Soviet palaces suddenly became symbols of resistance to the new anti-historicalism and conservative political isolationism. Nationalists demand their demolition, cosmopolitan youth throw their parties under their arches. The new Ukrainian techno scene feeds on the same spirit as the new cult of neo-modern architecture. I am trying to scroll through the chronicle of my perception of these spaces in the opposite direction in order to understand why they are so important to me, why they still feel like a kind of semantic support for the part of the world in which I live. And why does actual desolation and marginalization only sharpen this meaning? Another line of the exhibition is the images of “hero children”. Children and adolescents who participated in the anti-fascist resistance and partisan struggle during the Second World War became mythological figures in the post-war period. A secular cult of modern martyrs was built around their fates, and their portraits invariably looked at me sternly from school walls and from mosaics and reliefs in the same palaces of children’s creativity. Perhaps the children-heroes are the guardian spirits of modernist spaces, those who force us to return to the idea of history again and again, to pass between the Scylla of antihistoricism and the Charybdis of patriotic myth-making. The myth of “children-heroes” seems to be in eternal enmity with its own mythology, inventiveness, inventiveness, which are so transparent, so deliberate, as if at any moment they can fall off like shells, leaving us face to face with the question of our own readiness, the ability to face the wind of history. I see the faces of “children-heroes” in the guise of young Kiev ravers. And in the ornaments created in the 1980s at the Minskaya station, I see some strange and frightening faces. And here and there masks appear – persistently similar to the faces of the characters of Paul Klee. Angelus Novus quietly rustles its wings – and we hear the roar of rocket attacks in Donbas and techno parties in Kyiv. Painting gives space for the most vague guesses, the possibility of an accurate shot in the dark, a combination of infantile comfort and liberating horror of no one needs. In pursuit of old shadows, you can meet modernity by approaching it from the back. This will come as a surprise to both. | Voor zijn vierde tentoonstelling in galerie Transit koos Nikita Kadan [1982] ervoor terug te grijpen naar een ervaring die hij als kind beleefde maar die later in zijn puberteit, daarna als jong volwassene en nu in 2021 telkens een heel andere wending kreeg. De communistische kinder- en jeugdpaleizen, rijk versierd met mozaïeken, lijken nu pas belangrijk erfgoed te zijn, op het moment dat nationalisten ze willen afbreken en jongeren er rave-partys in organiseren. Kadan nodigde voor dit project ook de fotograaf Yevgen Nikiforov [1986] uit, die deze Oekraïense architectuur van de jaren 60-80 prachtig in beeld brengt. De titel van de tentoonstelling Children Are Surrounded by Art is ontleend aan een brochure uit de jaren zeventig over sanatoria, pionierspaleizen, kindervakantiekampen en de monumentale kunst die ze sierde. Hierin vond Kadan veel foto’s van kinderkampen op de Krim, neo-moderne gebouwen aan de Zwarte Zeekust, maar ook Oekraïense sovjetdecoratiekunst, die tegenwoordig actief wordt vernietigd in het kader van het ‘decommunisatiebeleid’. De Russische annexatie van de Krim en het anticommunisme van de Oekraïense staat hebben hun schaduw geworpen op de archiefbeelden, waardoor deze iets heel anders zijn geworden dan ze vóór 2014 waren. Deze veranderingen worden gedicteerd door de politieke geschiedenis, maar er is ook een emotionele geschiedenis. De immense, halfverduisterde zalen van de Sovjet-kinderkunstpaleizen waren voor hem als kind in de jaren tachtig een beeld van verveling en tijdverspilling. Later, als puber in de jaren negentig, waren het angstige en verleidelijke ruimten van verlatenheid en oncontroleerbaarheid, van vrijheid als iets wat niemand nodig had. In de jaren 2000 werden deze hallen volgebouwd met plastic kiosken en overdekt met reclamebanners, en werden ze de belichaming van ‘het eeuwige heden’ van het triomferende kapitalisme zonder enige historische dimensie (en zo ervaarde hij ze toen hij kunstenaar werd). In de jaren 2010 en ‘20 werden deze geleidelijk afbrokkelende, vervallen Sovjetpaleizen plots symbolen van verzet tegen het nieuwe anti-historicisme en het conservatieve politieke isolationisme. Nationalisten eisen hun vernietiging, maar kosmopolitische jongeren organiseren er rave-partys. Kadan probeert de tijdlijn van zijn perceptie van deze ruimtes terug te spoelen om te begrijpen waarom zij zo belangrijk voor hem zijn, waarom zij nog steeds aanvoelen als een ijkpunt van de wereld waarin hij leeft. Een andere lijn van de tentoonstelling zijn beelden van ‘kinderhelden’. De kinderen en adolescenten die deelnamen aan het antifascistische verzet en de partizanenstrijd tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog werden mythologische figuren in de naoorlogse periode. Rond hun lotgevallen werd een seculiere cultus van eigentijdse martelaren opgebouwd. Voor Kadan zijn de kinderhelden misschien wel de beschermgeesten van de modernistische ruimte. Zijn schilderkunst laat vage speculaties toe, maar is evenzeer een nauwkeurig schot in de duisternis. Bij het najagen van oude schaduwen kan je de moderniteit ontmoeten door haar te benaderen langs de achterkant. Kadan nodigde voor dit project ook de kunstenaar-fotograaf Yevgen Nikiforov [*1986] uit. Bijna elke Oekraïense stad of dorp heeft immers mozaïek-, reliëf- of glas-in-loodpanelen die in de jaren 1960-1980 door kunstenaars werden gemaakt. Deze kunstwerken, die bedoeld waren als versieringen voor openbare ruimten, werden nauwelijks echt waargenomen omdat de inwoners hun artistieke verdiensten nooit erkenden. Ze werden behandeld als propaganda in opdracht van de staat, die de aandacht niet waard was. Een van de redenen voor deze paradox is dat de USSR de openbare ruimte niet als zodanig heeft ontwikkeld, omdat de basisvrijheden daarvoor ontbraken: vrijheid van vergadering, protest en zelfexpressie. Nikiforov wil ze ontdoen van de opdringerige visuele ruis van post-Sovjetsteden die nooit helemaal over hun drang naar kapitalisme heen zijn gekomen. Sinds 2013 bezocht hij vijfhonderd steden en dorpen, legde tienduizenden kilometers af langs Oekraïense wegen en fotografeerde meer dan vijfduizend monumentale kunstwerken. Open: vrijdag, zaterdag & zondag, 14 – 18 uur & op afspraak via https://transit.be/plan-your-visit/ |

Reserved

Private collection

Private collection

Private collection

Private collection

Yevgen Nikiforov – photos

Kiev-palace-of-youth

Odessa

Yalta

Kyiv, Palats Ukraina Subway Station

Monument to the soldiers of the First Cavalry Army near Olesko, Lviv oblast, Ukraine. Monument is located next to the Kyiv–Lviv highway. Made from expensive copper, it has been gradually dismantled by locals for sale.

Monument to the soldiers of the First Cavalry Army near Olesko, Lviv oblast, Ukraine. Monument is located next to the Kyiv–Lviv highway. Made from expensive copper, it has been gradually dismantled by locals for sale.

Yevgen Nikiforov

ON REPUBLIC’S MONUMENTS

2014 – ongoing

In April 2015 Ukrainian Parliament approved the new law that condemned “the totalitarian Communist and Nazi regimes” and banned all related symbols and propaganda. Practically this so-called decommunization law means that all kind of USSR-related imagery including public art works depicting episodes from Soviet history and monuments of Communist leaders are to be demolished around the country. Most of centrally located monuments were pulled down quite rapidly, this process became known as “Leninfall”. But the further destiny of minor and remote ones is a bit more obscure as the political pressure isn’t that strong for local governments in smaller towns and villages. I started to shoot and research Soviet cultural heritage in all regions of Ukraine including Crimea when it had become clear that the nation’s attitude towards the Soviet past came to the point of complete reconsideration. My aim is to create a visual archive of once dominant and now vanishing elements of the cityscape, and to show different cases of how the symbols of the past have been reworked, vandalised, confusedly hidden and also mixed with new symbols referring to “patriotic identity” and thus appropriated by new political agenda. By analyzing this process in today’s Ukraine I also want to refer to a broader range of questions, such as how the visual emblems of the past still present in public spaces affect the collective memory and the ability to (de)construct historical narratives in both so called Eastern and Western societies in general.

Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics

2013 – ongoing

Almost every Ukrainian town has mosaic, relief or stained-glass panels created by Soviet artists in 1960s–1980s. Envisioned as decorations for public spaces, these art works were hardly ever really seen as residents never recognized their artistic merit. It was treated as state-commissioned propaganda, not worthy of attention. A reason for the paradox is that the USSR did not develop public space as such, lacking the basic freedoms to buttress it: freedom of assembly, protest and self-expression. For this ongoing series I’ve been visiting all regions in Ukraine since 2013 to photograph local monumental art pieces and establish their history. I want to present them clean of the intrusive visual noise of post-Soviet cities that never quite got over their gung-ho capitalism. My desire to defamiliarize the Soviet heritage had developed into 8 years of work. I visited more than 700 cities and villages, covering around 80,000 km of Ukrainian roads, discovered around 5,000 mosaics.